- Causes of Future Sea Level Rise

- Elevation Maps

- Will we really lose all that land?

- Sea Level Rise Planning Maps

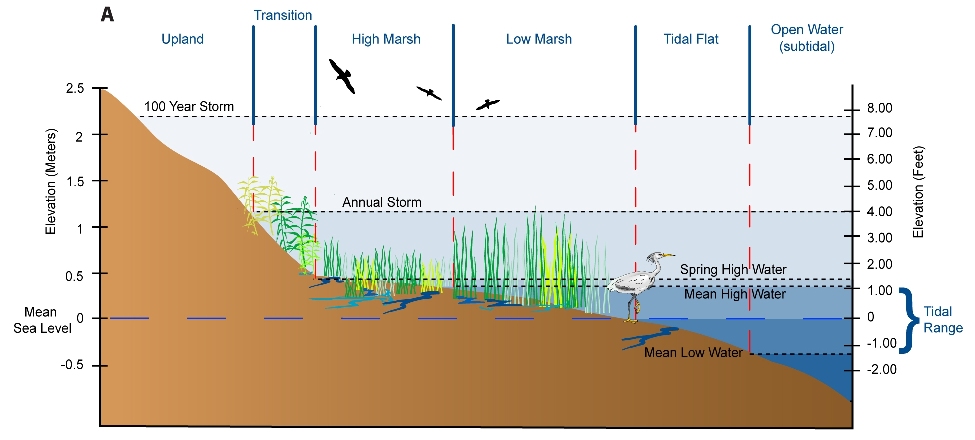

For purposes of rolling easements, a key difference between wetland shores and ocean beaches is that tidal flooding, rather than waves, governs the conversion from dry land to intertidal habitat (see Box 2).

Several consequences follow from this distinction:

- Land elevation rather than distance from the shore is the key predictor for how long a rising sea will take to convert dry land to wetlands. Land elevation is something that an owner can change by adding sand, soil, or other fill materials.

- Similarly, although the width of a natural beach is fairly constant for a given wave climate and sand size, the width of the strip of wetlands can vary greatly. While the inland and seaward boundaries of a beach retreat together, the inland and seaward boundaries of tidal wetlands can migrate independently: Migration of the inland wetland boundary as sea level rises depends primarily on land elevations, while retreat of the seaward boundary depends on wave erosion and the ability of the wetlands to keep pace through sedimentation and peat formation.

- Although beach nourishment and dune construction can move the beach seaward, they generally do not narrow the beach after an initial adjustment.[104] By contrast, efforts by owners to elevate dry land can narrow the wetlands by preventing their inland migration even while the seaward boundary erodes. Boat traffic can erode the seaward wetland boundary without causing the inland boundary to move inland.

- The inland boundary of tidal wetlands is not a straight line that is easy to discern.

- While storms often destroy homes along an eroding ocean shore within a few years after they encroach seaward of the dune vegetation line, homes along wetland shores are less vulnerable to storms.

- The confusing “law of avulsion”[105] is usually not an issue along wetland shores (except possibly in the five states where private land extends to mean low water). Although the seaward edge of tidal wetlands may erode suddenly during a storm, the mean high tide line retreats gradually inland as sea level rises.

Thus, for a rolling easement to ensure preservation of wetlands, it would generally have to prevent the landowner from adding fill to elevate the grade of the yard, or at least ensure a return to the original grade at some point in the future. As with a beachfront rolling easement, shore protection structures that stop the landward edge of the wetlands from migrating inland (e.g., bulkheads) must also be prohibited. Breakwaters, sills, and biologs that slow erosion of the outer marsh edge, by contrast, could be compatible with a rolling easement. Whether a rolling easement would have to directly require removal of homes in the wetlands would depend on site-specific factors beyond our scope here—but if removal is important, responsibility cannot be easily shifted to the next hurricane. Similarly, responsibility for site cleanup may have to be specifically allocated.

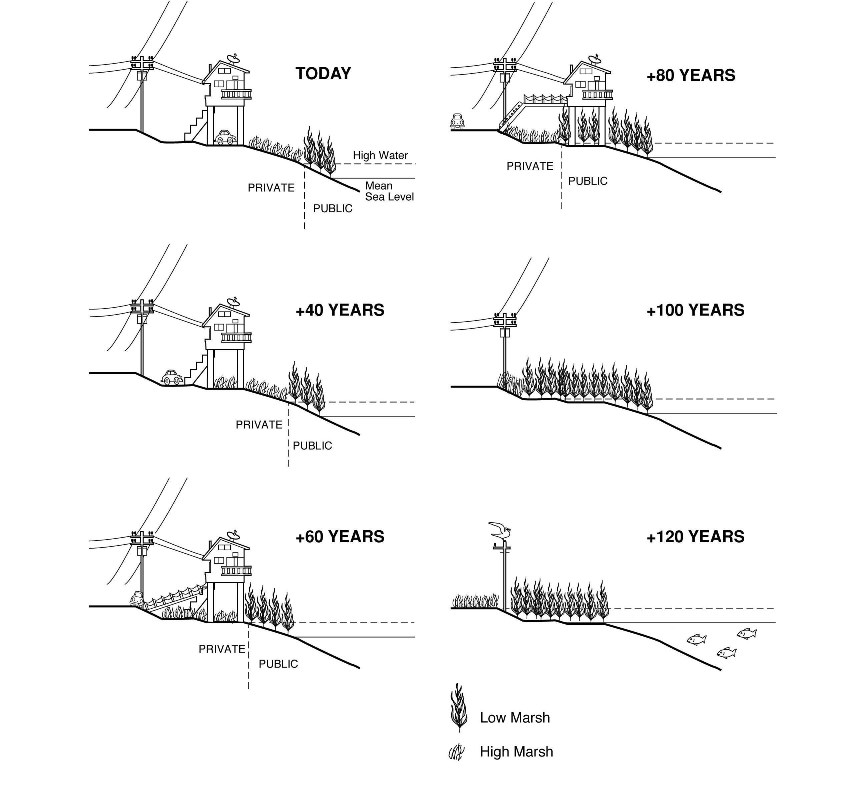

Figure 6 shows how this rolling easement could play out over time for the typical case where the private/public boundary is mean high water,[106] and therefore the high marsh is privately owned while the low marsh is publicly owned. A rolling easement allows construction near the shore, but requires the property owner to recognize nature’s right-of-way to advance inland as sea level rises. In the case depicted, the high marsh reaches the footprint of the house 40 years later. Because the house is on pilings, it can still be occupied, assuming that it is hooked to a sewerage treatment plant. (A flooded septic system would probably fail, because the drain field must be a minimum distance above the water table.) After 60 years, the marsh has advanced enough to require the owner to park her car along the street and construct a catwalk across the front yard. After 80 years, the marsh has taken over the entire yard; moreover, the footprint of the house is now seaward of mean high water, and hence is on public property. At this point, additional reinvestment in the property is unlikely. Twenty years later, the particular house has been removed, although other houses on the same street may still be occupied. Eventually, the entire area returns to nature.

This primer assumes that the mission of a rolling easement is accomplished once the rising sea submerges a given parcel.[107]In most cases, a rolling easement designed to allow wetlands to migrate inland will also enable the public/private boundary to move inland, because that boundary is either the mean low tide line (in five states), the mean high tide line (in most states), or another point defined based on the characteristics of the shore. At some point of submergence, privately owned land will become publicly owned water. Because an owner can never transfer that which she does not own, a rolling easement does not restrict what the state can do with the land once it is submerged and becomes wetland. In the rare case where a land trust believes that a state is likely to fill the wetlands once they become publicly owned, a rolling easement might not be advisable.[108]

As with sandy beaches, the public has an interest in both publicly and privately owned wetlands. The environmental interest includes all tidal wetlands, which generally extend inland to at least the spring high water line. But public ownership and public access generally only extends inland to mean high water under the public trust doctrine (ordinary high water for most states). [109] Hence, any restrictions may have to distinguish between migration of the upper edge of tidal wetlands and migration of the boundary between public trust wetlands and privately owned wetlands. (Chapter 6 considers the rolling design boundary in more detail.)

[104]

Assuming that the new sand is similar to what was already on the beach. The

width of the beach depends on the grain size of the sand and the wave climate,

with fine-grained sands and larger waves both causing a wider beach. See Per Bruun, Sea Level Rise as a Cause of Shore

Erosion, 88 Journal of

Waterways and Harbor Division. American Society of Civil Engineers

117–130 (1962).

[105]

See supra § 2.2.1 for a discussion of

the boundaries of public ownership and public access along tidal shores.

[106]

In five states, the boundary is mean low water; and in a few states the boundary

is a natural high water mark that may be above mean sea level due to waves. See supra notes 51–54

and accompanying text. In a few

places, where states have conveyed submerged lands to the owners of the adjacent

dry land, the boundary no longer moves with the shoreline. See supra note 57

and accompanying text.

[107]

The goal of the rolling easement is to prevent shore protection that would

eliminate the intertidal wetland, beach, or public access. Once the parcel is

submerged, shore protection is only possible if the land re-emerges and then

begins to submerge once again. If the land re-emerges suddenly (or gradually as

an island), the state is the new owner. If it emerges gradually and is connected

to some other land, it would belong to the owner of the adjacent land and

generally be subject to whatever conservation easements (if any) applied to that

parcel.

[108] A land trust and landowner may agree to elevate

the grade of high marsh, for example, which would be environmentally preferable

to the state filling the land and would

also

allow the landowner to retain title to the land. Living shoreline approaches may also be

viable. But these issues are

generally

best

left to those who manage the

rolling easement when the land submerges: a current

inclination by the state to fill wetlands would

have little bearing on what the state will

want

to do 100 years hence.

[109] See supra § 2.2.1 for a discussion of the boundaries of public ownership and access along

tidal shores

This page contains a section from: James G. Titus, Rolling Easements, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. EPA‑430‑R‑11‑001 (2011). The report was originally published by EPA's Climate Ready Estuary Program in June 2011. The full report (PDF, 176 pp., 7 MB) is also available from the EPA web site.

For additional reports focused on the implications of rising sea level, go to Sea Level Rise Reports.

2.3: Relocate Roads, Utilities and Parks Inland

2.3: Relocate Roads, Utilities and Parks Inland